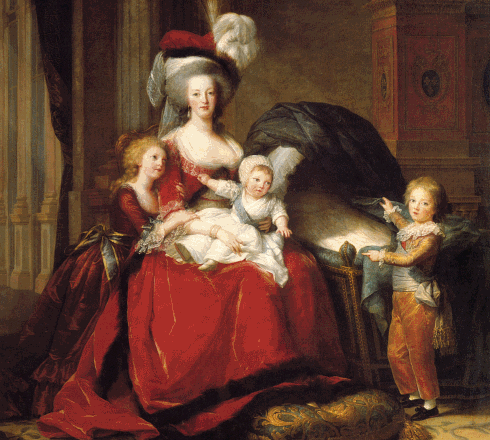

A painting of Marie Antoinette with her son, Louis-Charles, on her lap. (circa 1787)

A painting of Marie Antoinette with her son, Louis-Charles, on her lap. (circa 1787)

At the time of the French Revolution, the son of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, was known as Louis-Charles, Dauphin of France. He was abducted on August 10, 1792, when only eight years old, as the French revolution waged on.

When his parents were executed for treason under the first republic, the newly orphaned eight year old Louis-Charles would have been the nominal successor to the abolished throne.

He was imprisoned in the custody of a shoemaker named Antoine Simon. The Dauphin was kept in confinement and treated with great cruelty until he is said to have died in June 1795. He would have been 10 years old at the time of his death and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Rumors quickly spread that the body buried was not that of Louis-Charles and that he had been spirited away alive by sympathizers.

He had never been officially crowned as king, nor ruled. However, he was called by his royalist supporters Louis VII and the future Louis XVIII’s adoption of the title Louis XVIII rather than Louis XVII only added to the mystery.

Against this background, there is a legend that the Dauphin was taken secretly from his dungeon and brought clandestinely to northern New York, where there was a sizable population of Frenchmen still loyal to the monarchy. This strange story has been the subject of serious historical speculation for many years.

In the middle of the 1800’s, the Rev. John H. Hanson, an Episcopal priest, wrote a logical account of how a certain Eleazer Williams, an Episcopal priest of the North Country who died in 1858, might have been the lost Dauphin.

Williams was thought to be one of 12 children of Thomas Williams and grandson of Eunice Williams of Deerfield, Mass. who was one of the inhabitants captured by the Indians in the massacre of that village. Supposedly, eleven of Thomas Williams offspring bore unmistakable evidence of Indian heritage while Eleazer did not. Also, no record was ever made of Eleazer’s birth.

Williams himself claimed to have no knowledge of his own life before the age of twelve or thirteen. By his own account, he served in the War of 1812 as a scout and spy for American forces on the northern border of New York. After the war, he became an Episcopal missionary and was sent to the Oneida Tribe of upper New York State. He proved to be successful there, converting many of the Oneida to the Episcopal faith.

When the French monarchy was restored in 1814, hundreds of claimants came forward. Would-be royal heirs continued to appear across Europe for decades afterward.

In 1841, Prince de Joinville the younger son of Louis Phillip, the reigning King of France came to the United States. Williams would claim that the Prince had offered him a vast estate if only Williams would renounce his claim to the throne which he said he refused to do. The Prince denied this story as soon as he heard of it, saying that his only interest in Williams was as an Indian missionary.

In the February 1853, issue of Putnam’s Magazine, the Rev. Hanson, an Episcopal minister, published an article entitled “Have We A Bourbon Among Us?” That article also supported Williams’ claims. Serious historians immediately refuted Hanson’s speculations, but many others believed him and, for a while, Williams was something of a minor celebrity.

Williams died in the village of Hogansburg, NY on August 28, 1858.

The story did not die until 2000 when DNA testing proved beyond doubt that Louis-Charles had indeed died in prison.

Philippe-Jean Pelletan was one of the doctors who attended Louis-Charles shortly before his death and subsequently performed the autopsy. He removed the heart and this was not interred with the rest of Louis-Charles’s body. Philippe-Jean Pelletan tried to return Louis-Charles’s heart to Louis XVIII and Charles X, both of whom could not bring themselves to believe the heart to be that of their nephew.

The heart was stolen by one of Pelletan’s students, who confessed to the theft on his deathbed and asked his wife to return it to Pelletan. Instead, she sent it to the Archbishop of Paris, where it stayed until the Revolution of 1830. By 1975, it was being kept in a crystal vase at the royal crypt in outside Paris, the burial place of Louis-Charles’s parents and other members of France’s royal family.

In 2000 DNA testing was performed on the heart using samples from Marie-Antoinette, her sisters, their mother, Maria Theresa, and two living direct descendants in strict maternal line. The tests proved that the heart was that of Louis-Charles. It was buried in the Basilica on June 8, 2004 and forever dispelled the claims of the North Country preacher named Eleazer Williams.

(Compiled from online and print resources.)